Tengenenge – A hot spot of movement

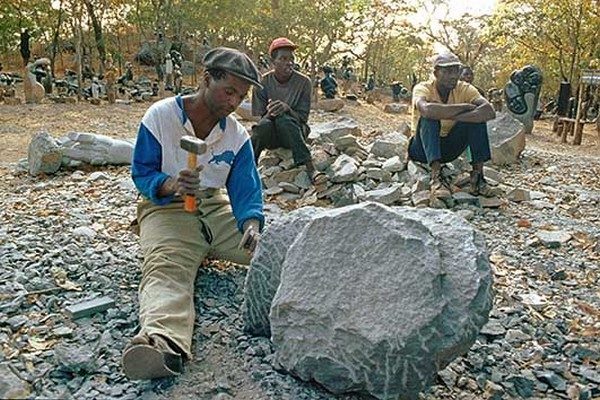

The village of Tengenenge takes us to the source of the movement.

Tengenenge, was founded by Tom Blomefield, in the late sixties in the North East of Zimbabwe. Blomefield had been a tobacco farmer in Guruve who, through the pressures of international sanctions after Ian Smith’s Declaration of Unilateral Independence (UDI), was no longer able to provide reliable employment for his farm workers – many of whom had travelled to Zimbabwe from Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia and Angola. In an effort to continue his support for these men and their families he encouraged them to make the change from farm labouring to art. The land on which the community was sited included an impressive natural deposit of hard, carveable Serpentine and it was to be stone carving for which his men became respected and applauded over the following twenty years. Frank McEwen and the National Gallery supported this community for several years, before the establishment of its own rural Workshop at Vukutu.

Tom Blomefield

Tengenenge then continued on its own path and still thrives today. As expressed in the quotation by Ulli Beier, about Frank McEwen, Blomefield had a similar, remarkable, ability to foster and extract latent talent from artistically untrained people. Like McEwen, he too has an infectious enthusiasm and gift of inspiring others, if not to create, then to would not have come about were it not for more these qualities. The two men, however, could not have had more different backgrounds and experiences on which to base their theories. With no artistic training and very little knowledge of the arts, Blomefield nevertheless felt passionately about the natural creative potential within the African people in Zimbabwe. Within an unshakeable (some would say naive) belief in the ability to live by simple means and personal resources in times of hardship, he displayed immense courage in implementing his ambitions. He first asked to be shown how to sculpt – approaching Chrispen Chakanuka. (…). After a short time of experimentation and hard work, he felt able to encourage anyone interested within the community around him. From such simple beginnings a movement was created which bore testimony to his beliefs and ideals. With similar, but less stringent guidelines as those practised by McEwen, he encouraged the emerging artists of Tengenenge to search their souls and create whatever they felt drawn to. He offered basic ‘criticism’ and advice if asked but in the main saw his role as a source of support. It is unquestionably due to this sensitive attitude that such extraordinary and unique talents found their expression: Lemon Moses, Bernard Matemara, Josiah Manzi, Wazi Maicolo, Amali Malola, Henry Munyaradzi, Sylvester Mubayi, Fanysani Akuda.

Some sculptors moved from the community to work on their own, or to join McEwen’s various groups – but all benefited incalculably from Blomefield’s generous spirit and sense of good.(…)

Difficulties within the country also heightened at this time and a ten-year internal struggle finally led to Independence for the new Zimbabwe in l980. The years of war represented an extremely difficult period for the sculptors. Many abandoned their art and returned to more conventional activities; many were unable to work in the rural areas as these became increasingly dangerous.(…) So it was then, that the responsibilities of the private promoters became more important. During the war years it was almost impossible to exhibit or sell work and individuals such as Roy Guthrie could only encourage and financially support the artists by purchasing works for the future exposure they believed possible in more peaceful times. Through this process Guthrie established strong friendships with the major artist of the time (John Takawira, Sylvester Mubayi, Joseph Ndandarika, Joram Mariga, Henry Munyaradzi, Bernard Takawira, Nicholas Mukomberanwa, Boira Mteki, Bernard Matemara), and at the first opportunity, began to organise definitive exhibitions abroad. These, in turn, aroused international interest that had existed previously and provided new impetus for the established artists as well as encouraging fresh, younger talent.

Currently, the community is always active and always welcomes 150 resident artists. It is a real town with a housing part (small houses and traditional huts) and a portion workshops and exhibitions (outdoors in the forest). Although Tengenenge is far from Harare, the capital, it is always interesting (Essential) to make a pilgrimage there to (re) plunge into the atmosphere of this high place of the movement of Zimbabwean contemporary artists.